On the evening of January 20, 2022, a car bomb struck the main gate of the al-Sina’a prison in the Ghuweyran neighborhood of al-Hasakah, in northeast Syria. Immediately following the bombing, 2 small ISIS cells entered the facility and began releasing prisoners. A large-scale riot broke out inside the prison which led to the guards being overpowered and their weapons taken. According to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an ISIS pickup truck also arrived a short time later to deliver a large cache of weapons to the prisoners, who subsequently barricaded themselves inside the facility and prepared for a counterattack.

The Islamic State’s affiliated news agency, Amaq, claimed that 2 more cells had been sent to simultaneously attack an oil depot and an SDF barracks close to the prison. The attack on the oil depot was intended to produce a smokescreen that would obstruct any aircraft attempting to conduct Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) in the area, whilst the attack on the barracks was aimed at slowing the response of a counter-offensive.

The attack turned into a 10-day-long battle between the ISIS militants held up in the prison and the SDF, with US-led coalition aircraft and special forces also becoming involved. On January 30, a statement was released by the US government claiming that the SDF had regained “full control” of the prison, and that sweep-up operations had commenced in the surrounding areas to capture the remaining escapees. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), a total of 154 members of the SDF and 346 ISIS militants had been killed in the fighting.

The al-Sina’a prison was the largest detention facility for ISIS fighters in northeast Syria. At the time of the attack, it held between 3,000 to 4,000 prisoners, including 700 minors. This made the facility an attractive target to the Islamic State.

So, how did the SDF fail to predict and prevent the attack from occurring?

Firstly, the facility was never intended to be a prison. As the Islamic State lost its last remaining territorial stronghold in the Syrian city of Baghouz, in 2019, the SDF was required to hastily establish a system of prisons capable of holding the overwhelming number of ISIS fighters and those suspected of having links to the group. The several former government prisons that the SDF had captured during the civil war were not enough, so they set up a series of makeshift detention centers in schools and industrial complexes to cater for the growing number of detainees. The al-Sina’a prison was one of those makeshift centers. According to the Middle East Institute, when the number of prisoners held at al-Hasakah’s central prison exceeded 2000 in spring 2019, the SDF seized a vocational education school down the road and turned it into an additional detention center.

In the following years, the al-Sina’a prison would experience a number of breakout attempts and uprisings, most of which were promptly suppressed by SDF forces. In one such incident, in March 2020, prisoners rioted and managed to seize control of the ground floor of one of the buildings, demanding that their conditions be improved. Within hours, the SDF had the situation under control.

By early 2021, the physical condition of al-Sina’a was rapidly deteriorating. In February, the British Ministry of Defense confirmed that it had approved funding for a “significant expansion” of the prison, which would meet international Red Cross standards once complete. However, there was no mention about whether these funds would be used to improve any security installations. As early as 2019, US defense officials had raised concerns about several issues at the prison, including the crumbling cement walls and security cameras that didn’t work or weren’t available. Already, a mass breakout was beginning to seem inevitable. Yet, despite the continuous warnings and repeated breakout attempts, the SDF remained reluctant to address the prison’s poor security standards. These precarious holding conditions were causing growing concern among the international community. Vladimir Voronkov, the Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations Counterterrorism Office, later described the January 2022 attack as “predictable”.

Most of the uprisings and breakout attempts at al-Sina’a had been planned from the inside. However, by late-2021 the SDF and their international partners were beginning to uncover a much larger breakout plot — one that was being planned and directed by some of the highest-ranking individuals in the Islamic State organization.

On November 8, 2021, the Asayish Anti-Terror Unit (HAT), with the support of SDF and coalition forces, conducted a pre-dawn raid against an ISIS cell in the village of Abu Kashab, in Deir ez-Zor governorate. According to the SDF, the HAT forces were tipped off to the cell planning a major jailbreak operation at the al-Sina’a prison in al-Hasakah. HAT forces also uncovered a large stockpile of weapons, documents and equipment that were intended to be used in the attack. A car bomb (VBIED) was also discovered at the property and destroyed by coalition aircraft. The SDF stated that one militant was killed and six others had been arrested during the raid.

This was considered one of the biggest operations of 2021 in northeast Syria. Kurdish authorities believed that their actions had thwarted a major attack on the prison. However, they had only just scratched the surface.

The following month, on December 19, an explosion occurred just down the road from al-Sina’a prison. Two people were injured. But no group claimed responsibility. The source of the explosion was a motorcycle IED, parked on the side of the street about 1 kilometer northwest of the prison and remotely detonated. Due to the lack of casualties, the incident was scarcely reported and quickly forgotten. It is unusual for the Islamic State to refrain from claiming an attack, no matter how small. It is also unlikely that this attack had been perpetrated by any other group. So, it is likely that this bombing was carried out by the Islamic State in order to test the response time of SDF units in the area.

Days later, on December 25, SDF and coalition special forces carried out a “complex joint security operation” that resulted in the capture of Mohammed Abid al-Awad, also known as “Rasheed”. According to a press statement released by the SDF, Rasheed was the leader of the cell responsible for the al-Sina’a prison attack plot that had been foiled in November, but he managed to escape and “disappear”. Rasheed was known to have been a leading figure in the Islamic State organization — in 2013, he joined Jabhat al-Nusra, before later defecting to ISIS. In 2014, he led the Islamic State’s tank and armored vehicle division during the siege of Kobani. After the Islamic State’s caliphate was defeated in 2019, he began using fake identities and remained ‘underground’ until his arrest in December, 2021.

Then, on January 17, 2022, SDF and coalition forces inserted by helicopter into the village of al-Hawaij, in Deir ez-Zor governorate, where they “neutralized” an unnamed ISIS leader who was also a member of the cell involved in the November prison attack plot. By this point, the SDF and their partners likely believed that, since they had dismantled most of the cell, an attack on the prison was no longer a possibility. However, they failed to realize that this plot was much bigger and involved multiple cells spread across the governorates of Deir-ez-Zor and al-Hasakah.

Time was ticking. Just 3 days later, the attack would begin.

The complexity of the attack demonstrated that a considerable amount of planning and preparation had gone into it. The SDF reported that a system of tunnels had been dug by ISIS sleeper cells between houses in the Ghuweyran and al-Zahour neighborhoods, to support the attack. Although, this has never been officially confirmed nor did ISIS make any reference to such a tactic in its detailed statement of the attack.

What is clear, is that the attack on al-Sina’a prison had been instructed from the very top of the Islamic State organization. According to a US government official cited by the Washington Post, the attack had been directed by the Islamic State’s overall leader at the time, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, who was killed by US special forces at his home in northern Syria just days after the attack came to an end. It is understood that the attack was one of the main reasons that al-Qurayshi was found, as the sudden escalation in ISIS activity following the prison break had caused an increase in the “flow of messengers” to his house, thus leaving him exposed.

Interestingly, the ISIS militants inside al-Sina’a also managed to establish a clear line of communication with the Islamic State’s central media department, which published 6 videos and numerous photos from inside the prison as the siege was still ongoing.

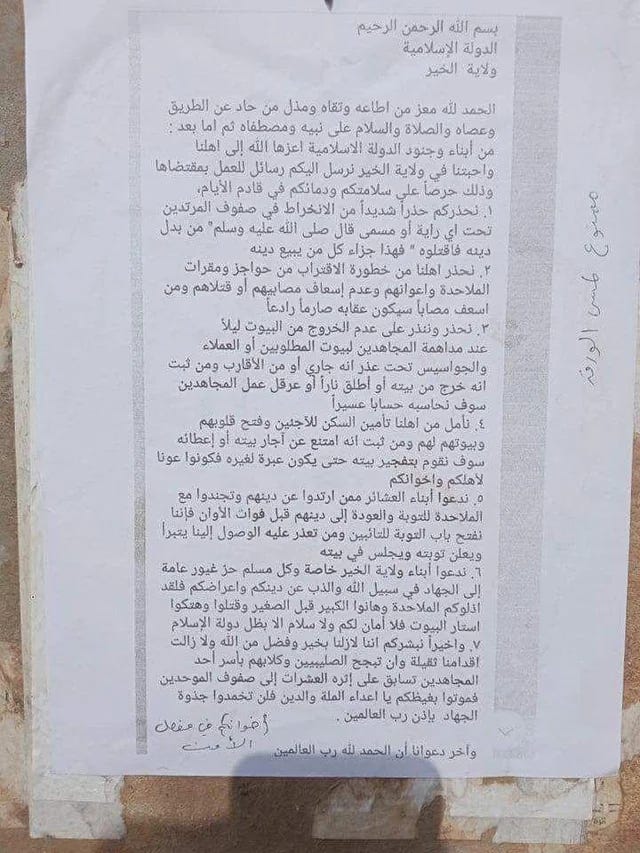

Further evidence of the intricate preparations that went into the attack came about one week prior to it commencing. The Islamic State had distributed flyers to residents in the villages of Swaydan Jazera, Darnaj, al-Jerthi, al-Sharqi, Abu Hardoub and Gharanij – all located in neighboring Deir ez-Zor governorate. The flyers warned that anyone who collaborated with the SDF would face “severe punishment”. Most notably, one line on the flyer stated that: “We hope that our people provide shelters for the displaced refugees and welcome them in their houses… if anyone refuses to rent or give his house to jihadists, we will blow up their house in order to be a lesson for not helping your brothers”. This line possibly suggests that an influx of ISIS escapees were expected to arrive in these villages once the prison attack had occurred, and that local residents should hospitably open their doors and provide them with shelter.

The failure to prevent the al-Sina’a prison attack can be traced back to a handful of errors in the months leading up to it. Had the SDF and their international partners been aware of how big the Islamic State’s operation was, they could have requested more support and allocated the necessary resources to track down the remaining cells. Instead, there seems to have been a belief that the attack was only being planned by a small number of ISIS operatives belonging to a single cell, and that the arrests made in November and January had put an end to their plan. There is also a possibility that the raid in November had sped up the Islamic State’s planning process and forced them to carry out the attack prematurely.

Whilst it is unlikely that the attack could have been completely avoided, its severity could have been mitigated if the SDF had addressed and repaired the deteriorating security conditions at the prison years ago, when they still had a chance to do so.

All that being said, I commend the efforts of the SDF and their partners for their persistence in the fight against ISIS. Degrading one of the most barbaric terror groups in recent history has been a valiant achievement.